Learn more about retinal eye care

What is retinal eye care? Conditions, treatment options and more!

At a Glance:

Things to know and remember:

- Diabetic eye disease comprises a group of eye conditions that affect people with diabetes. These conditions include diabetic retinopathy, diabetic macular edema (DME), cataract, and glaucoma.

- All forms of diabetic eye disease have the potential to cause severe vision loss and blindness.

- Macular Degeneration is a leading cause of blindness in people over 60.

- There are two forms of age-related macular degeneration -- dry and wet.

- AMD causes no pain, but an early symptom of wet AMD is that straight lines appear wavy. The most common symptom of dry AMD is slightly blurred vision.

- Symptoms of a retinal detachment include a sudden increase in the number of specks floating in your vision (floaters), flashes of light in one eye or both eyes, a “curtain” or shadow over your field of vision.

- Retinal detachment can happen to anyone. If you have an eye injury or trauma (like something hitting your eye), it’s important to see an eye doctor to check for early signs of retinal detachment

About Diabetic Eye Disease

What is diabetic eye disease?

Diabetic eye disease is a group of eye conditions that can affect people with diabetes.

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common diabetic eye disease. Diabetic retinopathy affects blood vessels in the light-sensitive tissue called the retina that lines the back of the eye. It is the most common cause of vision loss among people with diabetes and the leading cause of vision impairment and blindness among working-age adults.

Diabetic macular edema (DME). A consequence of diabetic retinopathy, DME is the build-up of fluid (edema) in a region of the retina called the macula. The macula is important for the sharp, straight-ahead vision that is used for reading, recognizing faces, and driving. DME is the most common cause of vision loss among people with diabetic retinopathy. About half of all people with diabetic retinopathy will develop DME. Although it is more likely to occur as diabetic retinopathy worsens, DME can happen at any stage of the disease.

Diabetic eye disease can also include cataract and glaucoma. Adults with diabetes are 2-5 times more likely than those without diabetes to develop cataract. Cataract also tends to develop at an earlier age in people with diabetes. With glaucoma, diabetes nearly doubles the risk of glaucoma in adults.

All forms of diabetic eye disease have the potential to cause severe vision loss and blindness. That’s why early diagnosis and treatment are always the best options for diabetic patients. In fact, because diabetic eye disease often goes unnoticed until vision loss occurs, people with diabetes should get a diabetic eye exam at least once a year.

There are generally two stages of diabetic retinopathy. Nonproliferative and proliferative. Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, the most common type of diabetic retinopathy, occurs when the blood vessels in a person’s retina weaken and tiny bulges protrude from their walls. Proliferative diabetic retinopathy is the most severe type of diabetic retinopathy and occurs with the growth of abnormal blood vessels. This may lead to bleeding or scar tissue formation, possibly causing detachment of the retina and permanent vision loss.

Diabetic retinopathy can develop in anyone who has Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes. The longer a person has diabetes, and the less controlled the blood sugar is, the more likely that person is to develop this disease. Between 40 and 45 percent of Americans diagnosed with diabetes have some stage of diabetic retinopathy, although only about half are aware of it. Women who develop or have diabetes during pregnancy may have rapid onset or worsening of diabetic retinopathy. Although it may cause no symptoms at all or mild vision problems, one must not forget that diabetic retinopathy can still result in blindness and must be treated.

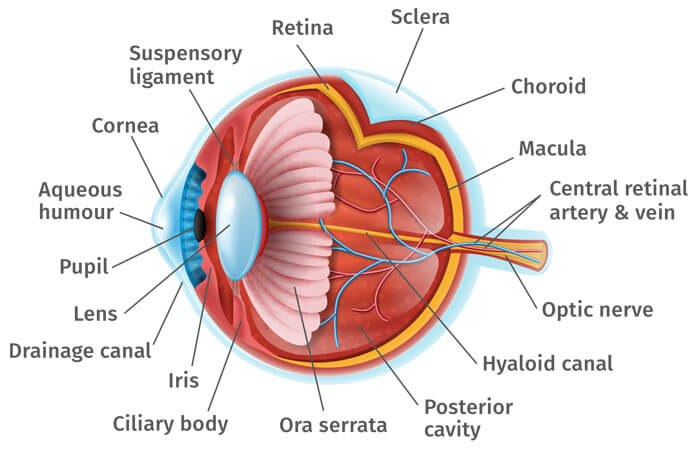

Chronically high blood sugar from diabetes is associated with damage to the tiny blood vessels in the retina, leading to diabetic retinopathy. The retina detects light and converts it to signals sent through the optic nerve to the brain. Diabetic retinopathy can cause blood vessels in the retina to leak fluid or hemorrhage (bleed), distorting vision. In its most advanced stage, new abnormal blood vessels proliferate (increase in number) on the surface of the retina, which can lead to scarring and cell loss in the retina.

Diabetic retinopathy may progress through four stages:

- Mild nonproliferative retinopathy. Small areas of balloon-like swelling in the retina’s tiny blood vessels, called microaneurysms, occur at this earliest stage of the disease. These microaneurysms may leak fluid into the retina.

- Moderate nonproliferative retinopathy. As the disease progresses, blood vessels that nourish the retina may swell and distort. They may also lose their ability to transport blood. Both conditions cause characteristic changes to the appearance of the retina and may contribute to DME.

- Severe nonproliferative retinopathy. Many more blood vessels are blocked, depriving blood supply to areas of the retina. These areas secrete growth factors that signal the retina to grow new blood vessels.

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). At this advanced stage, growth factors secreted by the retina trigger the proliferation of new blood vessels, which grow along the inside surface of the retina and into the vitreous gel, the fluid that fills the eye. The new blood vessels are fragile, which makes them more likely to leak and bleed. Accompanying scar tissue can contract and cause retinal detachment—the pulling away of the retina from underlying tissue, like wallpaper peeling away from a wall. Retinal detachment can lead to permanent vision loss.

The early stages of diabetic retinopathy usually have no symptoms. The disease often progresses unnoticed until it affects vision. Bleeding from abnormal retinal blood vessels can cause the appearance of “floating” spots. These spots sometimes clear on their own. But without prompt treatment, bleeding often recurs, increasing the risk of permanent vision loss. If DME occurs, it can cause blurred vision.

Diabetic retinopathy and DME are detected during a comprehensive dilated eye exam that includes:

- Visual acuity testing. This eye chart test measures a person’s ability to see at various distances.

- Tonometry. This test measures pressure inside the eye.

- Pupil dilation. Drops placed on the eye’s surface dilate (widen) the pupil, allowing a physician to examine the retina and optic nerve.

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT). This technique is similar to ultrasound but uses light waves instead of sound waves to capture images of tissues inside the body. OCT provides detailed images of tissues that can be penetrated by light, such as the eye.

A comprehensive dilated eye exam allows the doctor to check the retina for:

- Changes to blood vessels

- Leaking blood vessels or warning signs of leaky blood vessels, such as fatty deposits

- Swelling of the macula (DME)

- Changes in the lens

- Damage to nerve tissue

If DME or severe diabetic retinopathy is suspected, a fluorescein angiogram may be used to look for damaged or leaky blood vessels. In this test, a fluorescent dye is injected into the bloodstream, often into an arm vein. Pictures of the retinal blood vessels are taken as the dye reaches the eye.

Vision lost to diabetic retinopathy is sometimes irreversible; however, early detection and treatment can reduce the risk of blindness by 95 percent. Because diabetic retinopathy often lacks early symptoms, people with diabetes should get a comprehensive dilated eye exam at least once a year. People with diabetic retinopathy may need eye exams more frequently. Women with diabetes who become pregnant should have a comprehensive dilated eye exam as soon as possible. Additional exams during pregnancy may be needed.

Studies such as the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) have shown that controlling diabetes slows the onset and worsening of diabetic retinopathy. DCCT study participants who kept their blood glucose level as close to normal as possible were significantly less likely than those without optimal glucose control to develop diabetic retinopathy, as well as kidney and nerve diseases. Other trials have shown that controlling elevated blood pressure and cholesterol can reduce the risk of vision loss among people with diabetes.

Treatment for diabetic retinopathy is often delayed until it starts to progress to PDR, or when DME occurs. Comprehensive dilated eye exams are needed more frequently as diabetic retinopathy becomes more severe. People with severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy have a high risk of developing PDR and may need a comprehensive dilated eye exam as often as every 2 to 4 months.

Treatment options depend upon the nature of the diabetic eye disease but can include options from medications to laser surgery.

If nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy is present, treatment of the eye may not be necessary if blood sugar is well maintained. If proliferative diabetic retinopathy is present, laser procedures, surgeries, or injectable medications are available and may slow or stop the progression of diabetic retinopathy.

Based on your vision diagnosis during examination, our diabetic eye care specialists will discuss with you the most appropriate treatment options.

For decades, PDR has been treated with scatter laser surgery, sometimes called panretinal laser surgery or panretinal photocoagulation. Treatment involves making 1,000 to 2,000 tiny laser burns in areas of the retina away from the macula. These laser burns are intended to cause abnormal blood vessels to shrink. Although treatment can be completed in one session, two or more sessions are sometimes required. While it can preserve central vision, scatter laser surgery may cause some loss of side (peripheral), color, and night vision. Scatter laser surgery works best before new, fragile blood vessels have started to bleed. Recent studies have shown that anti-VEGF treatment not only is effective for treating DME, but is also effective for slowing progression of diabetic retinopathy, including PDR, so anti-VEGF is increasingly used as a first-line treatment for PDR.

In some cases of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), the new blood vessels can cause severe bleeding called a vitreous hemorrhage. This bleeding can block the vision and block the ability of your eye doctor to perform laser treatments. Further, neovascularization can lead to retinal detachment putting the patient at risk for severe vision loss. In these cases, your retinal specialist may recommend surgery to remove the blood or repair the retinal detachment.

In nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR), leaking blood vessels can cause macular edema and loss of vision. The goal of laser in NPDR is to stop the leakage and prevent further vision loss. In proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), neovascularization can cause severe loss of vision by bleeding (vitreous hemorrhage) and by developing scar tissue that can pull on the retina and cause a retinal detachment. The goal of laser in PDR is to stop the growth of new blood vessels and prevent these complications.

If the number of new vessels is great, laser treatment can often prevent loss of vision. The type of laser treatment that is done when there are a lot of vessels is called Panretinal Photocoagulation. This type of laser treatment is usually done in two or more separate sessions. The idea is to use the laser to destroy all of the dead areas of the retina where the blood vessels have been closed. When these areas are treated with the laser, the retina stops manufacturing new blood vessels, and those that are already present tend to diminish or disappear.

There are side effects of panretinal photocoagulation, and, for this reason, this treatment is not done when only a small number of new vessels are present. It is important to remember, however, that when the amount is great enough to warrant laser treatment, the longer the eye remains untreated the more likely vision will be lost, and blindness will occur. The earlier severe new vessels are discovered, and the eye is treated, the more likely blindness can be prevented. If you have developed any of these abnormal new vessels, your doctor will help advise you about when panretinal photocoagulation should be done.

Panretinal photocoagulation does not improve vision; it is just a means of holding vision stable to prevent further loss. After laser treatments, patients may still have reduced vision or may continue to lose more vision. But if laser is indicated, the chance is that laser treatment will prevent severe loss of vision.

Panretinal photocoagulation is placed on the side of the retina, not the center, and side vision will definitely be diminished. These side areas are sacrificed in order to save as much of the central vision as possible and to save the eye itself. Night vision will also be diminished. After laser, blurred vision is very common. Usually this blur goes away but in a small number of patients, some blur will continue forever.

DME can be treated with several therapies that may be used alone or in combination.

Anti-VEGF Injection Therapy. Anti-VEGF drugs are injected into the vitreous gel to block a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which can stimulate abnormal blood vessels to grow and leak fluid. Blocking VEGF can reverse abnormal blood vessel growth and decrease fluid in the retina. Available anti-VEGF drugs include Avastin (bevacizumab), Lucentis (ranibizumab), and Eylea (aflibercept). Lucentis and Eylea are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating DME. Avastin was approved by the FDA to treat cancer, but is commonly used to treat eye conditions, including DME.

The NEI-sponsored Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network compared Avastin, Lucentis, and Eylea in a clinical trial. The study found all three drugs to be safe and effective for treating most people with DME. Patients who started the trial with 20/40 or better vision experienced similar improvements in vision no matter which of the three drugs they were given. However, patients who started the trial with 20/50 or worse vision had greater improvements in vision with Eylea.

Most people require monthly anti-VEGF injections for the first six months of treatment. Thereafter, injections are needed less often: typically three to four during the second six months of treatment, about four during the second year of treatment, two in the third year, one in the fourth year, and none in the fifth year. Dilated eye exams may be needed less often as the disease stabilizes.

Avastin, Lucentis, and Eylea vary in cost and in how often they need to be injected, so patients may wish to discuss these issues with an eye care professional.

Focal/grid macular laser surgery. In focal/grid macular laser surgery, a few to hundreds of small laser burns are made to leaking blood vessels in areas of edema near the center of the macula. Laser burns for DME slow the leakage of fluid, reducing swelling in the retina. The procedure is usually completed in one session, but some people may need more than one treatment. Focal/grid laser is sometimes applied before anti-VEGF injections, sometimes on the same day or a few days after an anti-VEGF injection, and sometimes only when DME fails to improve adequately after six months of anti-VEGF therapy.

Corticosteroids. Corticosteroids, either injected or implanted into the eye, may be used alone or in combination with other drugs or laser surgery to treat DME. The Ozurdex (dexamethasone) implant is for short-term use, while the Iluvien (fluocinolone acetonide) implant is longer lasting. Both are biodegradable and release a sustained dose of corticosteroids to suppress DME. Corticosteroid use in the eye increases the risk of cataract and glaucoma. DME patients who use corticosteroids should be monitored for increased pressure in the eye and glaucoma.

A vitrectomy is the surgical removal of the vitreous gel in the center of the eye. The procedure is used to treat severe bleeding into the vitreous, and is performed under local or general anesthesia. Ports (temporary water-tight openings) are placed in the eye to allow the surgeon to insert and remove instruments, such as a tiny light or a small vacuum called a vitrector. A clear salt solution is gently pumped into the eye through one of the ports to maintain eye pressure during surgery and to replace the removed vitreous. The same instruments used during vitrectomy also may be used to remove scar tissue or to repair a detached retina.

Vitrectomy may be performed as an outpatient procedure or as an inpatient procedure, usually requiring a single overnight stay in the hospital. After treatment, the eye may be covered with a patch for days to weeks and may be red and sore. Drops may be applied to the eye to reduce inflammation and the risk of infection. If both eyes require vitrectomy, the second eye usually will be treated after the first eye has recovered.

About Macular Degeneration

What is macular degeneration?

Macular degeneration, or age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a leading cause of vision loss in Americans 60 and older. It is a disease that destroys your sharp, central vision. You need central vision to see objects clearly and to do tasks such as reading and driving.

AMD affects the macula, the part of the eye that allows you to see fine detail. It does not hurt, but it causes cells in the macula to die. In some cases, AMD advances so slowly that people notice little change in their vision. In others, the disease progresses faster and may lead to a loss of vision in both eyes. Regular comprehensive eye exams can detect macular degeneration before the disease causes vision loss. Treatment can slow vision loss. It does not restore vision.

The risk for AMD increases with age. AMD is most common in older people, but it can occur during middle age. Generally, though, the risk increases with age.

Other risk factors include:

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Caucasians are much more likely to lose vision from AMD than African-Americans

- Family history. People with a family history of AMD are at higher risk of getting the disease

- Women appear to be at greater risk than men

Your lifestyle can play a role in reducing your risk of developing AMD.

- Eat a healthy diet high in green leafy vegetables and fish

- Don't smoke

- Maintain normal blood pressure

- Watch your weight

- Exercise

AMD causes no pain.

AMD blurs the sharp central vision you need for straight-ahead activities such as reading, sewing, and driving. An early symptom of wet AMD is that straight lines appear wavy. The most common symptom of dry AMD is slightly blurred vision. You may have difficulty recognizing faces. You may need more light for reading and other tasks. Dry AMD generally affects both eyes, but vision can be lost in one eye while the other eye seems unaffected. As dry AMD gets worse, you may see a blurred spot in the center of your vision. Over time, as less of the macula functions, central vision in the affected eye can be lost gradually.

In some cases, AMD advances so slowly that people notice little change in their vision. In others, the disease progresses faster and may lead to a loss of vision in both eyes. AMD is a common eye condition among people age 50 and older. It is a leading cause of vision loss in older adults. And vision lost cannot be restored. That’s why early detection and treatment are so important. Make an appointment with one of our experienced macular degeneration specialists.

Yes. There are two forms of age-related macular degeneration -- dry and wet.

Wet AMD occurs when abnormal blood vessels behind the retina start to grow under the macula. These new blood vessels tend to be very fragile and often leak blood and fluid. The blood and fluid raise the macula from its normal place at the back of the eye.

Straight Lines Appear Wavy

An early symptom of wet AMD is that straight lines appear wavy. If you notice this condition or other changes to your vision, contact your eye care professional at once. You need a comprehensive dilated eye exam.

Wet AMD is More Severe

With wet AMD, loss of central vision can occur quickly. Wet AMD is considered to be advanced AMD and is more severe than the dry form.

Dry AMD occurs when the light-sensitive cells in the macula slowly break down, gradually blurring central vision in the affected eye. As dry AMD gets worse, you may see a blurred spot in the center of your vision. Over time, as less of the macula functions, central vision in the affected eye can be lost gradually.

The most common symptom of dry AMD is slightly blurred vision. You may have difficulty recognizing faces. You may need more light for reading and other tasks. Dry AMD generally affects both eyes, but vision can be lost in one eye while the other eye seems unaffected.

One of the most common early signs of dry AMD is drusen. Drusen are yellow deposits under the retina. They often are found in people over age 60. Your eye care professional can detect drusen during a comprehensive dilated eye exam.

Dry AMD has three stages -- early AMD, intermediate AMD, and advanced dry AMD. All of these may occur in one or both eyes.

People with early dry AMD have either several small drusen or a few medium-sized drusen. At this stage, there are no symptoms and no vision loss.

People with intermediate dry AMD have either many medium-sized drusen or one or more large drusen. Some people see a blurred spot in the center of their vision. More light may be needed for reading and other tasks.

In addition to drusen, people with advanced dry AMD have a breakdown of light-sensitive cells and supporting tissue in the macula. This breakdown can cause a blurred spot in the center of your vision.

Over time, the blurred spot may get bigger and darker, taking more of your central vision. You may have difficulty reading or recognizing faces until they are very close to you.

No. The wet form of AMD is considered Advanced AMD.

Yes. Both the wet form and the advanced dry form are considered advanced AMD. Vision loss occurs with either form. In most cases, only advanced AMD can cause vision loss.

Yes. All people who have the wet form had the dry form first. The dry form can advance and cause vision loss without turning into the wet form. The dry form also can suddenly turn into the wet form, even during early stage AMD. There is no way to tell if or when the dry form will turn into the wet form.

Dry AMD generally affects both eyes, but vision can be lost in one eye while the other eye seems unaffected. If you have vision loss from dry AMD in one eye only, you may not notice any changes in your overall vision. With the other eye seeing clearly, you can still drive, read, and see fine details. You may notice changes in your vision only if AMD affects both eyes. If you experience blurry vision, see an eye care professional for a comprehensive dilated eye exam.

Drusen are yellow deposits under the retina. They often are found in people over age 50. Your eye care professional can detect drusen during a comprehensive dilated eye exam.

Drusen alone do not usually cause vision loss. In fact, scientists are unclear about the connection between drusen and AMD. They do know that an increase in the size or number of drusen raises a person's risk of developing either advanced dry AMD or wet AMD. These changes can cause serious vision loss.

You should have a comprehensive dilated eye exam at least once a year. Your eye care professional can monitor your condition and check for other eye diseases. You may also be advised to take the AREDS supplementation.

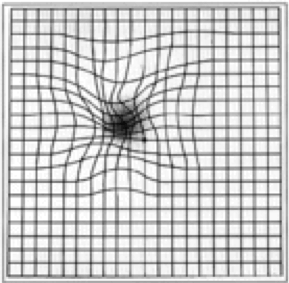

During an eye exam, you may be asked to look at an Amsler grid. You will cover one eye and stare at a black dot in the center of the grid. While staring at the dot, you may notice that the straight lines in the pattern appear wavy. You may notice that some of the lines are missing. These may be signs of AMD.

Because dry AMD can turn into wet AMD at any time, you should get an Amsler grid from your eye care professional. You could then use the grid every day to evaluate your vision for signs of wet AMD.

If you have lost some sight from AMD, ask your eye care professional about low vision services and devices that may help you make the most of your remaining vision.

Ask for a referral to a specialist in low vision. Many community organizations and agencies offer information about low vision counseling, training, and other special services for people with visual impairments.

Don't be afraid to use your eyes for reading, watching TV, and other routine activities. Normal use of your eyes will not cause further damage to your vision.

AMD is detected during a comprehensive eye exam that includes a multitude of tests. Tests for AMD include:

- The visual acuity test is an eye chart test that measures how well you see at various distances.

- In the dilated eye exam, drops are placed in your eyes to widen, or dilate, the pupils. Then, your eye care professional uses a special magnifying lens to examine your retina and optic nerve for signs of AMD and other eye problems. After the exam, your close-up vision may remain blurred for several hours.

- With tonometry, an instrument measures the pressure inside the eye. Numbing drops may be applied to your eye for this test.

Your eye care professional also may do other tests to learn more about the structure and health of your eye.

The Amsler Grid: During an eye exam, you may be asked to look at an Amsler grid, shown here. You will cover one eye and stare at a black dot in the center of the grid.

The Amsler Grid: During an eye exam, you may be asked to look at an Amsler grid, shown here. You will cover one eye and stare at a black dot in the center of the grid.

While staring at the dot, you may notice that the straight lines in the pattern appear wavy. You may notice that some of the lines are missing. These may be signs of AMD.

Because dry AMD can turn into wet AMD at any time, you should get an Amsler grid from your eye care professional. You could then use the grid every day to evaluate your vision for signs of wet AMD.

The Fluorescein Angiogram Test: If your eye care professional believes you need treatment for wet AMD, he or she may suggest a fluorescein angiogram. In this test, a special dye is injected into your arm. Pictures are taken as the dye passes through the blood vessels in your eye. The test allows your eye care professional to identify any leaking blood vessels and recommend treatment.

OCT: A procedure to measure retinal thickness.

Early treatment of intermediate AMD can delay and possibly prevent the advanced stages of AMD from occurring. When treating Wet AMD, the doctor will prescribe either injectable drug treatments, laser surgery, or photodynamic therapy based on the location and extent of the abnormal blood vessels. In rare cases, submacular hemorrhage displacement surgery may be used.

Once Dry AMD reaches the advanced stage, no form of treatment can prevent vision loss. However, treatment can delay and possibly prevent intermediate AMD from progressing to the advanced stage. The National Eye Institute's Age-Related Eye Disease Study found that taking certain vitamins and minerals may reduce the risk of developing advanced AMD.

Wet AMD can be treated with laser surgery, photodynamic therapy, and injections into the eye. None of these treatments is a cure for wet AMD. The disease and loss of vision may progress despite treatment.

Laser Surgery: Laser surgery uses a laser to destroy the fragile, leaky blood vessels. Only a small percentage of people with wet AMD can be treated with laser surgery. Laser surgery is performed in a doctor's office or eye clinic. The risk of new blood vessels developing after laser treatment is high. Repeated treatments may be necessary. In some cases, vision loss may progress despite repeated treatments.

Photodynamic Therapy: With photodynamic therapy, a drug called verteporfin is injected into your arm. It travels throughout the body, including the new blood vessels in your eye. The drug tends to stick to the surface of new blood vessels.

Next, the doctor shines a light into your eye for about 90 seconds. The light activates the drug. The activated drug destroys the new blood vessels and leads to a slower rate of vision decline.

Unlike laser surgery, verteporfin does not destroy surrounding healthy tissue. Because the drug is activated by light, you must avoid exposing your skin or eyes to direct sunlight or bright indoor light for five days after treatment. Photodynamic therapy is relatively painless. It takes about 20 minutes and can be performed in a doctor's office.

Photodynamic therapy slows the rate of vision loss. It does not stop vision loss or restore vision in eyes already damaged by advanced AMD. Treatment results often are temporary. You may need to be treated again.

Drug Treatment for Wet AMD: Wet AMD can now be treated with new drugs that are injected into the eye (anti-VEGF therapy). Abnormally high levels of a specific growth factor occur in eyes with wet AMD and promote the growth of abnormal new blood vessels. This drug treatment blocks the effects of the growth factor.

You will need multiple injections that may be given as often as monthly. The eye is numbed before each injection. After the injection, you will remain in the doctor's office for a while and your eye will be monitored. This drug treatment can help slow down vision loss from AMD and in some cases improve sight.

The AREDS formulation is a combination of antioxidants and zinc that is named for a study conducted by The National Eye Institute called the Age-Related Eye Disease Study, or AREDS. This study found that taking a specific high-dose formulation of antioxidants and zinc significantly reduced the risk of advanced AMD and its associated vision loss. Slowing AMD's progression from the intermediate stage to the advanced stage will save many people's vision.

The daily amounts used by the study researchers were 500 milligrams of vitamin C, 400 International Units of vitamin E, 15 milligrams of beta-carotene, 80 milligrams of zinc as zinc oxide, and 2 milligrams of copper as cupric oxide. Copper was added to the AREDS formulation containing zinc to prevent copper deficiency anemia, a condition associated with high levels of zinc intake.

People who are at high risk for developing advanced AMD should consider taking the formulation. You are at high risk for developing advanced AMD if you have either intermediate AMD in one or both eyes OR advanced AMD, dry or wet, in one eye but not the other eye.

Your eye care professional can tell you if you have AMD, its stage, and your risk for developing the advanced form. The AREDS formulation is not a cure for AMD. It will not restore vision already lost from the disease. However, it may delay the onset of advanced AMD. It may help people who are at high risk for developing advanced AMD keep their vision.

There is no reason for those diagnosed with early stage AMD to take the AREDS formulation. The study did not find that the formulation helped those with early stage AMD.

If you have early stage AMD, a comprehensive dilated eye exam every year can help determine if the disease is progressing. If early stage AMD progresses to the intermediate stage, discuss taking the formulation with your doctor.

The National Eye Institute is conducting and supporting a number of studies to learn more about AMD. For example, scientists are:

- studying the possibility of transplanting healthy cells into a diseased retina

- evaluating families with a history of AMD to understand genetic and hereditary factors that may cause the disease

- looking at certain anti-inflammatory treatments for the wet form of AMD

This research should provide better ways to detect, treat, and prevent vision loss in people with AMD.

About Retinal Detachment

What is retinal detachment?

Retinal detachment is an eye problem that happens when your retina (a light-sensitive layer of tissue in the back of your eye) is pulled away from its normal position at the back of your eye.

If only a small part of your retina has detached, you may not have any symptoms. But if more of your retina is detached, you may not be able to see as clearly as normal, and you may notice other sudden symptoms, including:

- A lot of new gray or black specks floating in your field of vision (floaters)

- Flashes of light in one eye or both eyes

- A dark shadow or “curtain” on the sides or in the middle of your field of vision

Important: Retinal detachment can be a medical emergency.

If you have symptoms of a detached retina, it’s important to go to your eye doctor or the emergency room right away.

The symptoms of retinal detachment often come on quickly. If the retinal detachment isn’t treated right away, more of the retina can detach — which increases the risk of permanent vision loss or blindness.

Anyone can have a retinal detachment, but some people are at higher risk. You are at higher risk if:

- You or a family member has had a retinal detachment before

- You’ve had a serious eye injury

- You’ve had eye surgery, like surgery to treat cataracts

Some other problems with your eyes may also put you at higher risk, including:

- Diabetic retinopathy (a condition in people with diabetes that affects blood vessels in the retina)

- Extreme nearsightedness (myopia), especially degenerative myopia

- Posterior vitreous detachment (when the gel-like fluid in the center of the eye pulls away from the retina)

- Certain other eye diseases, including retinoschisis or lattice degeneration

If you’re concerned about your risk for retinal detachment, talk with your eye doctor.

There are many causes of retinal detachment, but the most common causes are aging or an eye injury.

There are 3 types of retinal detachment: rhematogenous, tractional, and exudative. Each type happens because of a different problem that causes your retina to move away from the back of your eye.

There’s no way to prevent retinal detachment — but you can lower your risk by wearing safety goggles or other protective eye gear when doing risky activities like playing sports.

If you experience any symptoms of retinal detachment, go to your eye doctor or the emergency room right away. Early treatment can help prevent permanent vision loss.

It’s also important to get comprehensive dilated eye exams regularly. A dilated eye exam can help your eye doctor find a small retinal tear or detachment early, before it starts to affect your vision.

If you see any warning signs of a retinal detachment, your eye doctor can check your eyes with a dilated eye exam. The exam is simple and painless — your doctor will give you some eye drops to dilate (widen) your pupil and then look at your retina at the back of your eye.

If your eye doctor still needs more information after a dilated eye exam, you may get an ultrasound or an optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan of your eye. Both of these tests are painless and can help your eye doctor see the exact position of your retina.

Depending on how much of your retina is detached and what type of retinal detachment you have, your eye doctor may recommend laser surgery, freezing treatment, or other types of surgery to fix any tears or breaks in your retina and reattach your retina to the back of your eye. Sometimes, your eye doctor will use more than one of these treatments at the same time.

Freeze treatment (cryopexy) or laser surgery – If you have a small hole or tear in your retina, your doctor can use a freezing probe or a medical laser to seal any tears or breaks in your retina. You can usually get these treatments in the eye doctor’s office.

Surgery – If a larger part of your retina is detached from the back of your eye, you may need surgery to move your retina back into place. You will probably get these surgeries in a hospital.

Treatment for retinal detachment works well, especially if the detachment is caught early. In some cases, you may need a second treatment or surgery if your retina detaches again — but treatment is ultimately successful for about 9 out of 10 people.

Other Diseases Affecting the Retina and Macula

Most people know that having high blood pressure and heart disease is dangerous to your health. But did you know that high blood pressure can affect your vision too? Having high blood pressure can damage arteries that carry blood in the eye.

If a blood clot or cholesterol builds up and blocks blood flow in one or more of your retina’s arteries, it is called a retinal artery occlusion (RAO). This is like having a stroke (when blood flow to the brain is cut off), but in your eye instead of your brain.

There are two types of RAOs:

- Branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) blocks the small arteries in your retina.

- Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) is when the central artery in your retina becomes blocked. This is a form of a stroke in the eye and is a risk factor for having a brain stroke. CRAO is a serious emergency, just like a brain stroke, so it is important to go to a hospital Emergency Room right away to be checked and treated immediately.

What are symptoms of a retinal artery occlusion (RAO)?

The most common symptom of a retinal artery occlusion (RAO) is sudden, painless vision loss. You may lose vision in all of one eye (due to CRAO), or in part of one eye (from BRAO). In some cases, vision may have been lost in the past but come back again due to blood clots.

Other symptoms include the sudden appearance of:

- Complete loss of vision

- Loss of your side (peripheral) vision

- Distorted vision, where things may look wavy or out of shape

- Blind spots in your vision

If you have any of these symptoms, go to a hospital Emergency Room right away! Having a trained doctor quickly find and treat RAO can help prevent a brain stroke and may help save your vision.

Who is at risk for a retinal artery occlusion (RAO)?

RAO is most commonly found in people in their 60’s—especially men, though women can have it too. Having certain health problems increases your risk of RAO. These include:

- smoking

- obesity

- older age

- heart/lung disease

- diabetes

- high cholesterol

- high blood pressure

- narrowing of the carotid (neck) artery

- blood clotting problems

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology | Eye Smart

Your retina has veins and other blood vessels that carry blood. When a vein in your retina is blocked (occluded), it is called a retinal vein occlusion. This can be caused by a blood clot. Or it can happen when a larger blood vessel presses down on the vein.

With retinal vein occlusion, the blood vessels may become weaker and start to leak, which causes the macula to swell or thicken. This is called macular edema, and it leads to blurry vision or decreased vision.

With an occlusion, abnormal blood vessels can grow in your iris (colored part of your eye). This growth can cause painful pressure in the eye called neovascular (new blood vessels) glaucoma. New blood vessels may also grow in the retina, which can cause bleeding in the back of the eye and retinal detachment. This growth can cause painful pressure in the eye.

There are two types of retinal vein occlusion:

- CRVO (central retinal vein occlusion): This is when your eye’s main vein is blocked.

- BRVO (branch retinal vein occlusion): This is when small blood vessels attached to the eye’s main vein are blocked.

What causes retinal vein occlusion?

It is not known exactly what causes retinal vein occlusion. However, you are more likely to have retinal vein occlusion if you have:

- diabetes

- glaucoma (when high pressure inside the eye damages the optic nerve and causes vision loss)

- high blood pressure

- diseases related to blood vessels (vascular disease) or are obese

What are symptoms of retinal vein occlusion?

- blurry or less vision

- noticing a lot of floaters in your field of vision

- pain inside your eye if new blood vessels grow and cause high pressure in your eye

It is very important to call an ophthalmologist right away if you have any symptoms. They will check your eyes thoroughly and talk about treatment options. You may become blind or have permanently reduced vision if you do not have treatment for retinal vein occlusion.

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology | Eye Smart

Arteries and veins carry blood throughout your body, including your eyes. The eye’s retina has one main artery and one main vein. When the main retinal vein becomes blocked, it is called central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO).

When the vein is blocked, blood and fluid spills out into the retina. The macula can swell from this fluid, affecting your central vision. Eventually, without blood circulation, nerve cells in the eye can die and you can lose more vision.

What Are Symptoms of CRVO?

The most common symptom of CRVO is vision loss or blurry vision in part or all of one eye. It can happen suddenly or become worse over several hours or days. Sometimes, you can lose all vision suddenly.

You may notice floaters. These are dark spots, lines or squiggles in your vision. These are shadows from tiny clumps of blood leaking into the vitreous from retinal vessels.

In some more severe cases of CRVO, you may feel pain and pressure in the affected eye.

What Causes CRVO?

CRVO happens when a blood clot blocks the flow of blood through the retina’s main vein. Disease can make the walls of your arteries more narrow, which can lead to CRVO. Disease can stiffen the walls of your arteries, which in turn compress the main vein and lead to CRVO.

Who Is at Risk for CRVO?

CRVO usually happens in people who are 50 and older.

People who have the following health problems have a greater risk of CRVO:

- high blood pressure

- diabetes

- glaucoma

- hardening of the arteries (called arteriosclerosis)

To lower your risk for CRVO, you should do the following:

- eat a low-fat diet

- get regular exercise

- maintain an ideal weight

- don’t smoke

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology | Eye Smart

Arteries and veins carry blood throughout your body, including your eyes. The eye’s retina has one main artery and one main vein. When branches of the retinal vein become blocked, it is called branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO).

When the vein is blocked, blood and fluid spills out into the retina. The macula can swell from this fluid, affecting your central vision. Eventually, without blood circulation, nerve cells in the eye can die and you can lose more vision.

What Are the Symptoms of BRVO?

The most common symptom of branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) is vision loss or blurry vision in part of the eye. It can happen suddenly or become worse over several hours or days. Sometimes, you can lose all vision suddenly.

You may notice floaters. These are dark spots, lines or squiggles in your vision. These are shadows from tiny clumps of blood leaking into the vitreous from retinal vessels.

What Causes BRVO?

Many times doctors don’t know what causes the blockage in BRVO. Sometimes it can happen when disease makes the walls of your arteries thicker and harder. Those arteries can cross over and put pressure on a vein.

Who Is at Risk for BRVO?

Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) usually happens in people who are aged 50 and older.

People who have the following health problems have a greater risk of BRVO:

- high blood pressure

- diabetes

- glaucoma

- hardening of the arteries (called arteriosclerosis)

To lower your risk for BRVO, you should do the following:

- eat a low-fat diet

- get regular exercise

- maintain an ideal weight

- don’t smoke

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology | Eye Smart

The middle of the eye is filled with a substance called vitreous. In the healthy, young eye, this clear, gel-like substance is firmly attached to the retina and the macula by millions of microscopic fibers. As the eye ages, or as a result of eye disease, the vitreous shrinks and pulls away from the retina. The vitreous, over time, separates completely from the retina. This is called a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) and is usually a normal part of aging. It happens to most people by age 70.

In some people with PVD, the vitreous doesn’t detach completely. Part of the vitreous remains stuck to the macula, at the center of the retina. The vitreous pulls and tugs on the macula, causing vitreomacular traction (VMT). This can damage the macula and cause vision loss if left untreated.

What Causes Vitreomacular Traction?

VMT is usually caused by part of the vitreous remaining stuck to the macula during a posterior vitreous detachment.

People with certain eye diseases may be at a higher risk for VMT, including those with:

- high myopia (extreme nearsightedness)

- age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (a breakdown of tissues in the back of the eye)

- diabetic eye disease (disease that affects the blood vessels in the back of the eye)

- retinal vein occlusion (a blockage of veins in the retina)

Also, taking pilocarpine to treat age-related blurry near vision (presbyopia) can increase your risk of VMT.

What Are Symptoms of Vitreomacular Traction?

The most common symptoms of vitreomacular traction (VMT) include:

- distorted vision that makes a grid of straight lines appear wavy, blurry, or blank.

- seeing flashes of light in your vision

- seeing objects as smaller than their actual size

These symptoms can also be a sign of another eye disease. This is why it’s important to see an ophthalmologist for an evaluation when you first notice any of these symptoms.

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology | Eye Smart

Macular edema happens when fluid builds up in the macula, causing swelling. This can distort vision, making things look blurry and colors look washed out. Without treatment, macular edema can even lead to permanent vision loss.

Cause

Macular edema is caused by pockets of fluid (usually leakage from damaged blood vessels) swelling up in the macula. There are many conditions that can leak fluid into the retina and cause macular edema, including:

- Diabetes

- Age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

- Macular pucker/vitreomacular traction

- Retinal vein occlusion (RVO)

- Hereditary/genetic disorders (passed from parent to child), such as retinoschisis or retinitis pigmentosa

- Inflammatory eye diseases

- Medication

- Eye tumors, both benign and malignant

- Eye surgery (less common)

- Injuries or trauma to the eye

Symptoms

Macular edema is painless and usually doesn’t have symptoms when you first get it. When you do have symptoms, they are a sign that the blood vessels in your eye may be leaking.

Common symptoms of macular edema include:

- blurred or wavy central vision

- colors appear washed out or different

- having difficulty reading

If you notice any macular edema symptoms, see an ophthalmologist as soon as possible. If left untreated, macular edema can cause severe vision loss and even blindness.

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology | Eye Smart

Macular hole is when a circular opening forms in your macula. As the hole forms, things in your central vision will look blurry, wavy or distorted. As the hole grows, a dark or blind spot appears in your central vision. A macular hole does not affect your peripheral (side) vision.

What Causes a Macular Hole?

Age is the most common cause of macular hole. As you get older, the vitreous begins to shrink and pull away from the retina. Usually the vitreous pulls away with no problems. But sometimes the vitreous can stick to the retina. This causes the macula to stretch and a hole to form. Sometimes a macular hole can form when the macula swells from other eye disease. Or it can be caused by an eye injury.

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology | Eye Smart

Macular pucker (also called epiretinal membrane) happens when wrinkles, creases or bulges form on your macula. The macula must lie flat against the back of your eye to work properly. When the macula wrinkles or bulges, your central vision is affected.

With macular pucker, things can look wavy, or you may have trouble seeing details. You might notice a gray, cloudy, or a blank area in your central vision. You may even have waviness in your central vision where straight lines look crooked or wavy. Macular pucker will not affect your peripheral (side) vision.

What causes macular pucker?

Age is the most common cause of macular pucker. As you get older, the vitreous begins to shrink and pull away from the retina. Usually the vitreous pulls away with no problems. But sometimes the vitreous can stick to the retina. Scar tissue forms, causing the retina and macula to wrinkle or bulge.

Who is at risk for macular pucker?

Aging is the most common risk factor for macular pucker. People who have other eye problems may also get a macular pucker. These problems include:

- Posterior vitreous detachment, where the eye’s vitreous pulls away from the retina

- Torn or detached retina

- Swelling inside the eye

- Previous surgery or serious damage to the eye from injury

- Problems with blood vessels in the retina

- Diabetes

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology | Eye Smart

Macular telangiectasia (MacTel) is a disease affecting the macula, causing loss of central vision. MacTel develops when there are problems with the tiny blood vessels around the fovea. The fovea, in the center of the macula, gives us our sharpest central vision for activities like reading. There are two types of MacTel, and each affects the blood vessels differently.

Type 2 MacTel

The tiny blood vessels around the fovea become abnormal and may dilate (widen). It is not known what causes MacTel. In some cases, new blood vessels form under the retina. This is called macular neovascularization. These blood vessels leak fluid or bleed. Fluid from leaking blood vessels causes the macula to swell or thicken, which affects your central vision. Also, tissue in the macula or the fovea may thin out or form a scar, causing loss of detail vision. Type 2 affects both eyes but not always with the same severity.

Type 1 MacTel

In Type 1 MacTel, the blood vessels dilate and tiny aneurysms form, which leak and cause swelling. This is called macular edema and it damages macular cells. The disease almost always occurs in one eye, which differentiates it from Type 2.

Symptoms of Macular Telangiectasia

In the early stages, people with MacTel will have no symptoms. As the disease progresses, you may have blurring, distorted vision, and loss of central vision. You may need brighter light to read or perform other functions. Loss of central vision progresses over a period of 10 – 20 years. MacTel does not affect side vision and does not usually cause total blindness.

Because MacTel has no early symptoms, it is important to get regular eye exams. This allows your ophthalmologist to detect any macular problems as early as possible.

Who is at risk for Macular Telangiectasia?

Type 2 MacTel happens most often in middle-aged adults. Both men and women are equally affected. If you have diabetes or hypertension, you may be at increased risk. The disease seems to run in some families, so there may be a genetic predisposition. This is not yet completely understood. In most cases, there is no known cause for the disease.

Type 1 MacTel is associated with Coat’s disease. This is a rare eye disorder present from birth, and is found almost entirely in males. Type 1 MacTel is usually diagnosed around age 40.

Source: American Academy of Ophthalmology | Eye Smart

Does my insurance plan

cover my eye care?

Find out what insurance we accept and what is covered by insurance.

Learn more about our retinal eye care specialists

Physician information including education, training, practice location and more.

Schedule an Appointment

Schedule an appointment with one of our specialists.